What Plants And Animals Did Lewis And Clark Discover

Route of the expedition on a map with modern borders

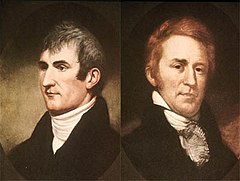

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, as well known as the Corps of Discovery Trek, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country afterward the Louisiana Buy. The Corps of Discovery was a select group of U.S. Regular army and civilian volunteers under the control of Helm Meriwether Lewis and his close friend Second Lieutenant William Clark. Clark and 30 members set out from Camp Dubois, Illinois, on May 14, 1804, and met Lewis and 10 other members of the group in St. Louis, Missouri. The expedition crossed the Continental Separate of the Americas and reached the Pacific Sea in 1805. The return voyage began on March 23, 1806, and ended on September 23 of the aforementioned yr.

President Thomas Jefferson commissioned the trek soon after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 to explore and to map the newly acquired territory, to find a practical route across the western half of the continent, and to establish an American presence in this territory earlier European powers attempted to establish claims in the region. The entrada'south secondary objectives were scientific and economical: to study the area'due south plants, animate being life, and geography, and to establish trade with local Native American tribes. The expedition returned to St. Louis to report its findings to Jefferson, with maps, sketches, and journals in hand.[1] [2]

Overview

I of Thomas Jefferson's goals was to detect "the well-nigh straight and practicable water advice across this continent, for the purposes of commerce." He too placed special importance on declaring US sovereignty over the land occupied past the many dissimilar Native American tribes forth the Missouri River, and getting an accurate sense of the resources in the recently completed Louisiana Purchase.[3] [4] [five] [6] The expedition made notable contributions to scientific discipline,[7] only scientific research was not the primary goal of the mission.[8]

During the 19th century, references to Lewis and Clark "scarcely appeared" in history books, fifty-fifty during the United States Centennial in 1876, and the trek was largely forgotten.[nine] [10] Lewis and Clark began to gain attention around the showtime of the 20th century. Both the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis and the 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon, showcased them every bit American pioneers. However, the story remained relatively shallow until mid-century equally a celebration of Us conquest and personal adventures, just more than recently the expedition has been more thoroughly researched.[9]

In 2004, a complete and reliable set of the expedition's journals was compiled by Gary East. Moulton.[xi] [12] [13] In the 2000s, the bicentennial of the expedition further elevated pop interest in Lewis and Clark.[10] As of 1984, no US exploration party was more famous, and no American expedition leaders are more than recognizable by name.[9]

Timeline

The timeline covers the chief events associated with the expedition, from January 1803 through January 1807.

Preparations

For years, Thomas Jefferson read accounts about the ventures of diverse explorers in the western frontier, and consequently had a long-held interest in farther exploring this more often than not unknown region of the continent. In the 1780s, while Minister to France, Jefferson met John Ledyard in Paris and they discussed a possible trip to the Pacific Northwest.[fourteen] [15] Jefferson had also read Captain James Melt'south A Voyage to the Pacific Sea (London, 1784), an account of Cook's third voyage, and Le Page du Pratz'southward The History of Louisiana (London, 1763), all of which greatly influenced his decision to send an trek. Like Captain Cook, he wished to discover a applied route through the Northwest to the Pacific declension. Alexander Mackenzie had already charted a route in his quest for the Pacific, following Canada's Mackenzie River to the Arctic Ocean in 1789. Mackenzie and his party were the first to cross America northward of United mexican states, reaching the Pacific coast in British Columbia in 1793–a dozen years before Lewis and Clark. Mackenzie's accounts in Voyages from Montreal (1801) informed Jefferson of Britain'due south intent to establish control over the lucrative fur trade of the Columbia River and convinced him of the importance of securing the territory as soon as possible.[16] [17] At Philadelphia, Israel Whelan, the purveyor of public supplies, purchased supplies for the trek afterwards a list provided by Lewis. Among the purchased items were found 193 pounds of portable soup, 130 rolls of pigtail tobacco, thirty gallons of strong spirit of wine, a wide assortment of Indian presents, medical and surgical supplies, mosquito netting and oilskin bags.[18]

Two years into his presidency, Jefferson asked Congress to fund an expedition through the Louisiana territory to the Pacific Sea. He did not attempt to make a clandestine of the Lewis and Clark trek from Spanish, French, and British officials, simply rather claimed different reasons for the venture. He used a secret message to enquire for funding due to poor relations with the opposition Federalist Political party in Congress.[19] [xx] [21] [22] Congress subsequently appropriated $2,324 for supplies and nutrient, the appropriation of which was left in Lewis'southward accuse.[23]

In 1803, Jefferson deputed the Corps of Discovery and named Ground forces Captain Meriwether Lewis its leader, who then invited William Clark to co-lead the expedition with him.[24] Lewis demonstrated remarkable skills and potential as a frontiersman, and Jefferson made efforts to prepare him for the long journey ahead every bit the expedition was gaining approval and funding.[25] [26] Jefferson explained his pick of Lewis:

It was impossible to find a character who to a complete science in botany, natural history, mineralogy & astronomy, joined the firmness of constitution & character, prudence, habits adapted to the wood & a familiarity with the Indian manners and grapheme, requisite for this undertaking. All the latter qualifications Capt. Lewis has.[27]

In 1803, Jefferson sent Lewis to Philadelphia to study medicinal cures under Benjamin Rush, a md and humanitarian. He as well arranged for Lewis to be farther educated past Andrew Ellicott, an astronomer who instructed him in the employ of the sextant and other navigational instruments.[28] [29] From Benjamin Smith Barton, Lewis learned how to describe and preserve plant and brute specimens, from Robert Patterson refinements in computing breadth and longitude, while Caspar Wistar covered fossils, and the search for possible living remnants.[30] [31] Lewis, however, was not ignorant of science and had demonstrated a marked capacity to learn, especially with Jefferson as his teacher. At Monticello, Jefferson possessed an enormous library on the subject of the geography of the North American continent, and Lewis had total admission to it. He spent time consulting maps and books and conferring with Jefferson.[32]

The keelboat used for the starting time yr of the journey was built almost Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the summer of 1803 at Lewis's specifications. The boat was completed on August 31 and was immediately loaded with equipment and provisions. While in Pittsburgh, Lewis bought a Newfoundland dog, Seaman, to back-trail them. Newfoundlands are working dogs and adept swimmers; normally constitute on fishing boats, they can aid in water rescues. Seaman proved a valuable fellow member of the party, helping with hunting and protection from bears and other wild animals. He was the only creature to complete the entire trip.

Lewis and his crew set canvas that afternoon, traveling downwardly the Ohio River to meet up with Clark most Louisville, Kentucky in October 1803 at the Falls of the Ohio.[33] [34] Their goals were to explore the vast territory acquired by the Louisiana Purchase and to plant trade and US sovereignty over the Native Americans along the Missouri River. Jefferson also wanted to found a US claim of "discovery" to the Pacific Northwest and Oregon territory by documenting an American presence there before European nations could claim the land.[five] [35] [36] [37] Co-ordinate to some historians, Jefferson understood that he would take a better claim of ownership to the Pacific Northwest if the squad gathered scientific information on animals and plants.[38] [39] Yet, his main objectives were centered around finding an all-water route to the Pacific coast and commerce. His instructions to the expedition stated:

The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri River, & such principle stream of information technology, as, by its form and communication with the waters of the Pacific ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado or any other river may offer the almost direct & practicable h2o communication across this continent for the purpose of commerce.[twoscore]

Camp Dubois (Camp Forest) reconstruction, where the Corps of Discovery mustered through the wintertime of 1803–1804 to expect the transfer of the Louisiana Buy to the United states

The U.s.a. mint prepared special silvery medals with a portrait of Jefferson and inscribed with a message of friendship and peace, chosen Indian Peace Medals. The soldiers were to distribute them to the tribes that they met. The expedition likewise prepared advanced weapons to display their military firepower. Among these was an Austrian-fabricated .46 quotient Girandoni air rifle, a repeating rifle with a xx-round tubular magazine that was powerful enough to kill a deer.[41] [42] [43] The expedition was prepared with flintlock firearms, knives, blacksmithing supplies, and cartography equipment. They also carried flags, gift bundles, medicine, and other items that they would need for their journey.[41] [42] The route of Lewis and Clark's expedition took them up the Missouri River to its headwaters, so on to the Pacific Ocean via the Columbia River, and information technology may have been influenced past the purported transcontinental journey of Moncacht-Apé by the same route about a century earlier. Jefferson had a copy of Le Page's book in his library detailing Moncacht-Apé's itinerary, and Lewis carried a copy with him during the expedition. Le Folio'due south description of Moncacht-Apé'southward route across the continent neglects to mention the need to cantankerous the Rocky Mountains, and information technology might be the source of Lewis and Clark'south mistaken conventionalities that they could easily conduct boats from the Missouri's headwaters to the w-flowing Columbia.[44]

Journey

Departure

The Corps of Discovery departed from Camp Dubois (Camp Wood) at 4pm on May 14, 1804. Under Clark'southward command, they traveled upwardly the Missouri River in their keelboat and two pirogues to St. Charles, Missouri where Lewis joined them six days afterward. The trek set out the next afternoon, May 21.[45] While accounts vary, it is believed the Corps had as many as 45 members, including the officers, enlisted armed forces personnel, civilian volunteers, and Clark'south African-American slave York.[46]

From St. Charles, the expedition followed the Missouri through what is now Kansas City, Missouri, and Omaha, Nebraska. On August xx, 1804, Sergeant Charles Floyd died, apparently from acute appendicitis. He had been among the first to sign up with the Corps of Discovery and was the only member to die during the expedition. He was buried at a barefaced by the river, now named after him,[47] in what is now Sioux City, Iowa. His burying site was marked with a cedar post on which was inscribed his name and twenty-four hours of decease. one mile (2 km) upward the river, the expedition camped at a small river which they named Floyd's River.[48] [49] [50] During the final week of August, Lewis and Clark reached the edge of the Great Plains, a identify abounding with elk, deer, bison, and beavers.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition established relations with two dozen Indian nations, without whose assistance the expedition would accept risked starvation during the harsh winters or become hopelessly lost in the vast ranges of the Rocky Mountains.[51]

The Americans and the Lakota nation (whom the Americans chosen Sioux or "Teton-wan Sioux") had problems when they met, and there was a business the ii sides might fight. Co-ordinate to Harry West. Fritz, "All before Missouri River travelers had warned of this powerful and aggressive tribe, adamant to cake free trade on the river. ... The Sioux were also expecting a retaliatory raid from the Omaha Indians, to the due south. A recent Sioux raid had killed 75 Omaha men, burned forty lodges, and taken four dozen prisoners."[52] The expedition held talks with the Lakota near the confluence of the Missouri and Bad Rivers in what is at present Fort Pierre, South Dakota.[53]

Reconstruction of Fort Mandan, Lewis and Clark Memorial Park, North Dakota

One of their horses disappeared, and they believed the Sioux were responsible. Afterward, the ii sides met and in that location was a disagreement, and the Sioux asked the men to stay or to give more gifts instead before being allowed to pass through their territory. They came shut to fighting several times, and both sides finally backed down and the expedition continued on to Arikara territory. Clark wrote they[ clarification needed ] were "warlike" and were the "vilest miscreants of the savage race".[54] [55] [56] [57]

In the winter of 1804–05, the political party congenital Fort Mandan, near present-day Washburn, North Dakota. Just before parting on April seven, 1805, the expedition sent the keelboat back to St. Louis with a sample of specimens, some never seen earlier due east of the Mississippi.[58] One main asked Lewis and Clark to provide a gunkhole for passage through their national territory. As tensions increased, Lewis and Clark prepared to fight, only the two sides fell dorsum in the end. The Americans quickly continued w (upriver), and camped for the winter in the Mandan nation's territory.

Later the expedition had prepare up camp, nearby Indians came to visit in off-white numbers, some staying all night. For several days, Lewis and Clark met in council with Mandan chiefs. Hither they met a French-Canadian fur trapper named Toussaint Charbonneau, and his young Shoshone married woman Sacagawea. Charbonneau at this time began to serve as the expedition's translator. Peace was established between the expedition and the Mandan chiefs with the sharing of a Mandan ceremonial pipe.[59] By April 25, Captain Lewis wrote his progress report of the expedition'due south activities and observations of the Native American nations they have encountered to engagement: A Statistical view of the Indian nations inhabiting the Territory of Louisiana, which outlined the names of various tribes, their locations, trading practices, and water routes used, among other things. President Jefferson would later nowadays this report to Congress.[lx]

Lewis and Clark Coming together the Salish in Ross Hole, September 4, 1805.

They followed the Missouri to its headwaters, and over the Continental Divide at Lemhi Pass. In canoes, they descended the mountains by the Clearwater River, the Serpent River, and the Columbia River, past Celilo Falls, and by what is now Portland, Oregon, at the meeting of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers. Lewis and Clark used William Robert Broughton'due south 1792 notes and maps to orient themselves in one case they reached the lower Columbia River. The sighting of Mount Hood and other stratovolcanos confirmed that the expedition had almost reached the Pacific Ocean.[61]

Pacific Ocean

Fort Clatsop reconstruction on the Columbia River near the Pacific Ocean

The expedition sighted the Pacific Body of water for the first time on November 7, 1805, arriving two weeks later.[62] [63] The expedition faced its 2d bitter wintertime camped on the north side of the Columbia River, in a storm-wracked area.[62] Lack of food was a major gene. The elk, the political party's primary source of food, had retreated from their usual haunts into the mountains, and the party was now besides poor to purchase enough food from neighboring tribes.[64] On November 24, 1805, the party voted to motility their camp to the south side of the Columbia River near modernistic Astoria, Oregon. Sacagawea, and Clark'southward slave York, were both immune to participate in the vote.[65]

On the southward side of the Columbia River, 2 miles (three km) upstream on the w side of the Netul River (now Lewis and Clark River), they constructed Fort Clatsop.[62] They did this not just for shelter and protection, but likewise to officially plant the American presence there, with the American flag flying over the fort.[55] [66] During the winter at Fort Clatsop, Lewis committed himself to writing. He filled many pages of his journals with valuable cognition, mostly nearly phytology, because of the abundant growth and forests that covered that part of the continent.[67] The wellness of the men also became a trouble, with many suffering from colds and flu.[64]

Knowing that maritime fur traders sometimes visited the lower Columbia River, Lewis and Clark repeatedly asked the local Chinooks about trading ships. They learned that Captain Samuel Loma had been at that place in early on 1805. Miscommunication caused Clark to tape the proper name every bit "Haley". Captain Hill returned in November 1805, and anchored about 10 miles (16 km) from Fort Clatsop. The Chinook told Colina about Lewis and Clark, but no direct contact was made.[68]

Return trip

Lewis was determined to remain at the fort until April 1, but was nevertheless anxious to move out at the primeval opportunity. By March 22, the stormy weather had subsided and the post-obit morning time, on March 23, 1806, the journeying home began. The Corps began their journey homeward using canoes to ascend the Columbia River, and later on by trekking over state.[69] [70]

Before leaving, Clark gave the Chinook a letter to requite to the side by side ship helm to visit, which was the same Captain Hill who had been nearby during the wintertime. Hill took the letter to Canton and had information technology forwarded to Thomas Jefferson, who thus received it earlier Lewis and Clark returned.[68]

They made their way to Campsite Chopunnish[annotation 1] in Idaho, along the north depository financial institution of the Clearwater River, where the members of the expedition nerveless 65 horses in grooming to cross the Bitterroot Mountains, lying between modernistic-twenty-four hour period Idaho and western Montana. Still, the range was still covered in snow, which prevented the trek from making the crossing. On April 11, while the Corps was waiting for the snowfall to diminish, Lewis's domestic dog, Seaman, was stolen by Native Americans, merely was retrieved shortly. Worried that other such acts might follow, Lewis warned the main that whatever other wrongdoing or mischievous acts would result in instant death.

On July three, before crossing the Continental Carve up, the Corps split up into ii teams so Lewis could explore the Marias River. Lewis's grouping of four met some men from the Blackfeet nation. During the night, the Blackfeet tried to steal their weapons. In the struggle, the soldiers killed two Blackfeet men. Lewis, George Drouillard, and the Field brothers fled over 100 miles (160 kilometres) in a day before they camped again.

Meanwhile, Clark had entered the Crow tribe's territory. In the night, half of Clark'south horses disappeared, only non a single Crow had been seen. Lewis and Clark stayed separated until they reached the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers on August 11. As the groups reunited, one of Clark'due south hunters, Pierre Cruzatte, mistook Lewis for an elk and fired, injuring Lewis in the thigh.[71] One time together, the Corps was able to render home quickly via the Missouri River. They reached St. Louis on September 23, 1806.[72]

Castilian interference

In March 1804, before the expedition began in May, the Spanish in New United mexican states learned from General James Wilkinson[note two] that the Americans were encroaching on territory claimed by Kingdom of spain. Later on the Lewis and Clark expedition gear up off in May, the Spanish sent four armed expeditions of 52 soldiers, mercenaries[ further explanation needed ], and Native Americans on August 1, 1804, from Santa Fe, New Mexico north under Pedro Vial and José Jarvet to intercept Lewis and Clark and imprison the entire expedition. They reached the Pawnee settlement on the Platte River in central Nebraska and learned that the trek had been at that place many days before. The expedition was covering lxx to 80 miles (110 to 130 km) a solar day and Vial's endeavor to intercept them was unsuccessful.[73] [74]

Geography and science

Map of Lewis and Clark'southward expedition: It inverse mapping of northwest America by providing the starting time authentic depiction of the relationship of the sources of the Columbia and Missouri Rivers, and the Rocky Mountains around 1814

The Lewis and Clark Expedition gained an agreement of the geography of the Northwest and produced the start accurate maps of the surface area. During the journey, Lewis and Clark drew about 140 maps. Stephen Ambrose says the expedition "filled in the main outlines" of the area.[75]

The trek documented natural resource and plants that had been previously unknown to Euro-Americans, though not to the indigenous peoples.[76] Lewis and Clark were the beginning Americans to cantankerous the Continental Separate, and the first Americans to run into Yellowstone, enter into Montana, and produce an official clarification of these different regions.[77] [78] Their visit to the Pacific Northwest, maps, and proclamations of sovereignty with medals and flags were legal steps needed to claim championship to each ethnic nation's lands nether the Doctrine of Discovery.[79]

The trek was sponsored past the American Philosophical Society (APS).[fourscore] Lewis and Clark received some instruction in astronomy, botany, climatology, ethnology, geography, meteorology, mineralogy, ornithology, and zoology.[81] During the expedition, they made contact with over 70 Native American tribes and described more than than 200 new plant and creature species.[82]

Jefferson had the expedition declare "sovereignty" and demonstrate their military force to ensure native tribes would be subordinate to the U.South., equally European colonizers did elsewhere. Subsequently the expedition, the maps that were produced allowed the farther discovery and settlement of this vast territory in the years that followed.[83] [84]

In 1807, Patrick Gass, a individual in the U.S. Army, published an account of the journey. He was promoted to sergeant during the course of the expedition.[85] Paul Allen edited a two-book history of the Lewis and Clark expedition that was published in 1814, in Philadelphia, merely without mention of the actual author, banker Nicholas Biddle.[86] Even then, the complete report was not fabricated public until more recently.[87] The earliest authorized edition of the Lewis and Clark journals resides in the Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library at the University of Montana.

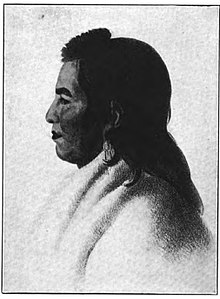

Encounters with Native Americans

1 of the trek'due south primary objectives as directed by President Jefferson was to exist a surveillance mission that would report back the whereabouts, military force, lives, activities, and cultures of the various Native American tribes that inhabited the territory newly acquired past the United States as part of the Louisiana Purchase and the northwest in general. The trek was to make native people sympathize that their lands at present belonged to the The states and that "their corking male parent" in Washington was now their sovereign.[88] The expedition encountered many different native nations and tribes along the style, many of whom offered their assistance, providing the trek with their cognition of the wilderness and with the acquisition of food. The expedition had blank leather-spring journals and ink for the purpose of recording such encounters, besides equally for scientific and geological information. They were too provided with various gifts of medals, ribbons, needles, mirrors, and other manufactures which were intended to ease any tensions when negotiating their passage with the various Indian chiefs whom they would encounter along their way.[89] [90] [91] [92]

Many of the tribes had friendly experiences with British and French fur traders in various isolated encounters along the Missouri and Columbia Rivers, and for the well-nigh part the expedition did not meet hostilities. However, in that location was a tense confrontation on September 25, 1804, with the Teton-Sioux tribe (besides known as the Lakota people, one of the three tribes that comprise the Great Sioux Nation), nether chiefs that included Black Buffalo and the Partisan. These chiefs confronted the expedition and demanded tribute from the expedition for their passage over the river.[89] [90] [91] [92] The vii native tribes that comprised the Lakota people controlled a vast inland empire and expected gifts from strangers who wished to navigate their rivers or to pass through their lands.[93] According to Harry Westward. Fritz, "All earlier Missouri River travelers had warned of this powerful and aggressive tribe, adamant to block gratis trade on the river. ... The Sioux were besides expecting a retaliatory raid from the Omaha Indians, to the southward. A contempo Sioux raid had killed 75 Omaha men, burned 40 lodges, and taken 4 dozen prisoners."[94]

Captain Lewis made his start mistake by offering the Sioux principal gifts get-go, which insulted and angered the Partisan chief. Advice was difficult, since the expedition's only Sioux language interpreter was Pierre Dorion who had stayed behind with the other party and was as well involved with diplomatic affairs with another tribe. Consequently, both chiefs were offered a few gifts, but neither was satisfied and they wanted some gifts for their warriors and tribe. At that bespeak, some of the warriors from the Partisan tribe took hold of their boat and one of the oars. Lewis took a business firm stand, ordering a brandish of force and presenting arms; Captain Clark brandished his sword and threatened violent reprisal. Just earlier the situation erupted into a violent confrontation, Blackness Buffalo ordered his warriors to dorsum off.[89] [ninety] [91] [92]

The captains were able to negotiate their passage without further incident with the aid of better gifts and a bottle of whiskey. During the side by side 2 days, the expedition fabricated camp not far from Black Buffalo's tribe. Similar incidents occurred when they tried to leave, simply trouble was averted with gifts of tobacco.[89] [xc] [91] [92]

Observations

As the expedition encountered the various Native American tribes during the grade of their journeying, they observed and recorded information regarding their lifestyles, community and the social codes they lived past, as directed by President Jefferson. Past European standards, the Native American manner of life seemed harsh and unforgiving as witnessed by members of the trek. Later many encounters and camping in shut proximity to the Native American nations for extended periods of time during the winter months, they presently learned first hand of their customs and social orders.

One of the primary customs that distinguished Native American cultures from those of the West was that it was customary for the men to take on ii or more wives if they were able to provide for them and frequently took on a wife or wives who were members of the immediate family unit circle, e.g. men in the Minnetaree [note 3] and Mandan tribes would often take on a sister for a wife. Guiltlessness among women was not held in high regard. Infant daughters were oft sold by the begetter to men who were grown, usually for horses or mules.[ citation needed ]

They learned that women in Sioux nations were oftentimes bartered away for horses or other supplies, still this was non skillful among the Shoshone nation who held their women in college regard.[95] They witnessed that many of the Native American nations were constantly at war with other tribes, specially the Sioux, who, while remaining by and large friendly to the white fur traders, had proudly boasted of and justified the virtually complete destruction of the once great Cahokia nation, along with the Missouris, Illinois, Kaskaskia, and Piorias tribes that lived about the countryside next to the upper Mississippi and Missouri rivers.[96]

Sacagawea

Statue of Sacagawea, a Shoshone woman who accompanied the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Sacagawea, sometimes spelled Sakajawea or Sakagawea (c. 1788 – December 20, 1812), was a Shoshone Native American adult female who arrived with her husband and owner Toussaint Charbonneau on the expedition to the Pacific Bounding main.

On February xi, 1805, a few weeks after her first contact with the trek, Sacagawea went into labor which was irksome and painful, and so the Frenchman Charbonneau suggested she be given a potion of rattlesnake's rattle to aid in her delivery. Lewis happened to accept some serpent's rattle with him. A short time after administering the potion, she delivered a healthy boy who was given the proper name Jean Baptiste Charbonneau.[97] [98]

When the expedition reached Marias River, on June 16, 1805, Sacagawea became dangerously ill. She was able to observe some relief by drinking mineral h2o from the sulphur spring that fed into the river.[99]

Though she has been discussed in literature frequently, much of the information is exaggeration or fiction. Scholars say she did notice some geographical features, but "Sacagawea ... was not the guide for the Expedition, she was important to them as an interpreter and in other ways."[100] The sight of a woman and her infant son would accept been reassuring to some indigenous nations, and she played an important part in diplomatic relations past talking to chiefs, easing tensions, and giving the impression of a peaceful mission.[101] [102]

In his writings, Meriwether Lewis presented a somewhat negative view of her, though Clark had a college regard for her, and provided some support for her children in subsequent years. In the journals, they used the terms "squar" (squaw) and "savages" to refer to Sacagawea and other indigenous peoples.[103]

York

An enslaved blackness man known only as York took part in the expedition as personal retainer to William Clark, his owner. York did much to aid the trek succeed. He proved pop with the Native Americans, who had never seen a black man. He also helped with hunting and the heavy labor of pulling boats upstream. Expecting his liberty later the expedition, he was disappointed when Clark refused repeatedly. While all the other explorers enjoyed rewards of double pay and land, York received nothing. Clark would not let York to remain in Louisville with his married woman and probably children. He whipped York, put him in jail, and somewhen sold him. The last years of York'due south life are disputed. In the 1830s, a black human being who said he had first come with Lewis & Clark was living equally a master with Indians they met on the expedition, in mod Wyoming.

Accomplishments

The Corps met their objective of reaching the Pacific, mapping and establishing their presence for a legal claim to the land. They established diplomatic relations and merchandise with at least two dozen indigenous nations. They did not find a continuous waterway to the Pacific Ocean[104] but located an Indian trail that led from the upper stop of the Missouri River to the Columbia River which ran to the Pacific Ocean.[105] They gained data nigh the natural habitat, flora and animate being, bringing back various institute, seed and mineral specimens. They mapped the topography of the land, designating the location of mountain ranges, rivers and the many Native American tribes during the course of their journey. They likewise learned and recorded much about the language and customs of the Indian tribes they encountered, and brought back many of their artifacts, including bows, vesture and ceremonial robes.[106]

Aftermath

Painting of Mandan Chief Big White, who accompanied Lewis and Clark on their return from the expedition

Two months passed afterward the expedition's end before Jefferson made his first public argument to Congress and others, giving a 1-judgement summary about the success of the expedition before getting into the justification for the expenses involved. In the course of their journeying, they acquired a noesis of numerous tribes of Native Americans hitherto unknown; they informed themselves of the trade which may exist carried on with them, the best channels and positions for information technology, and they are enabled to give with accuracy the geography of the line they pursued. Back east, the botanical and zoological discoveries drew the intense interest of the American Philosophical Order who requested specimens, diverse artifacts traded with the Native Americans, and reports on plants and wild fauna along with various seeds obtained. Jefferson used seeds from "Missouri hominy corn" along with a number of other unidentified seeds to found at Monticello which he cultivated and studied. He later reported on the "Indian corn" he had grown as being an "splendid" food source.[107] The expedition helped establish the U.S. presence in the newly acquired territory and across and opened the door to further exploration, trade and scientific discoveries.[108]

Lewis and Clark returned from their trek, bringing with them the Mandan Native American Chief Shehaka from the Upper Missouri to visit the "Great Father" in Washington. Later Chief Shehaka's visit, information technology required multiple attempts and multiple military expeditions to safely return Shehaka to his nation.

Legacy and honors

In the 1970s, the federal government memorialized the winter associates encampment, Camp Dubois, as the kickoff of the Lewis and Clark voyage of discovery and in 2019 it recognized Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania equally the start of the expedition.[109]

Since the expedition, Lewis and Clark have been commemorated and honored over the years on diverse coins, currency, and commemorative postage stamps, besides every bit in a number of other capacities. In 2004, the American elm cultivar Ulmus americana 'Lewis & Clark' (selling name Prairie Expedition) was released past Due north Dakota State Academy Research Foundation in commemoration of the trek's bicentenary;[110] the tree has a resistance to Dutch elm disease.

The Lewis and Clark Public School District in North Dakota is named after the pair.

-

Lewis and Clark Expedition, 2004

200th Anniversary result U.S. postage stamp commemorating the 200th anniversary of the Expedition -

Lewis and Clark Expedition

150th anniversary issue, 1954 -

Lewis & Clark were honored (forth with the American bison) on the Series of 1901 $10 Legal Tender

-

Lewis and Clark Mosaic image in Missouri

Prior discoveries

In 1682, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle traveled down the Mississippi from the Smashing Lakes to the Gulf. The French and then established a concatenation of posts along the Mississippi from New Orleans to the Smashing Lakes. In that location followed a number of French explorers including Pedro Vial and Pierre Antoine and Paul Mallet, amid others. Vial may have preceded Lewis and Clark to Montana. In 1787, he gave a map of the upper Missouri River and locations of "territories transited by Pedro Vial" to Spanish authorities.[111]

Early in 1792, the American explorer Robert Gray, sailing in the Columbia Rediviva, discovered the even so to exist named Columbia River, named it after his ship and claimed it for the United states. After in 1792, the Vancouver Expedition had learned of Gray's discovery and used his maps. Vancouver's expedition explored over 100 miles (160 km) upwardly the Columbia, into the Columbia River Gorge. Lewis and Clark used the maps produced by these expeditions when they descended the lower Columbia to the Pacific coast.[112] [113]

From 1792 to 1793, Alexander Mackenzie had crossed N America from Quebec to the Pacific.[114]

See as well

- Timeline of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

- The Far Horizons, a film about the expedition

- Gateway Curvation National Park

- Lewis and Clark Pass (Montana) – the but non-motorized pass on the expedition'due south road

- Lewis and Clark'southward Keelboat

- The Red River Expedition (1806) and the Pike Expedition were also commissioned by Jefferson

- James Kendall Hosmer American history professor and librarian who edited and published Nicholas Biddle's account of Lewis and Clark'due south periodical

Notes

- ^ 'Chopunnish' was the Captain's term for the Nez Perce Pass

- ^ Later on Wilkinson died in 1825, information technology was discovered that he was a spy for the Spanish crown.

- ^ aka the Hidatsa

References

- ^ Woodger, Toropov, 2009 p. 150

- ^ Ambrose, 1996, Chap. 6

- ^ Miller, 2006 p. 108

- ^ Fenelon & Wilson, 2006 pp. xc–91

- ^ a b Lavender, 2001 pp.32, 90

- ^ Ronda, 1984 pp. 82, 192

- ^ Fritz, 2004 p. 113

- ^ Ronda, 1984 p. 9

- ^ a b c Ronda, 1984 pp. 327–28

- ^ a b Fresonke & Spence, 2004 pp. 159–62

- ^ Moulton, 2004

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 p. 480

- ^ Saindon, 2003 pp. 6, 1040

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 p. 69

- ^ Grey, 2004 p. 358

- ^ DeVoto, 1997 p. xxix

- ^ Schwantes, 1996 pp. 54–55

- ^ Cutright 1969, p. 27.

- ^ Rodriguez, 2002 p. xxiv

- ^ Furtwangler, 1993 p. 19

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 p. 83

- ^ Bergon, 2003, p. xiv

- ^ Jackson, 1993, pp. 136–137

- ^ Ambrose, pp. 98-99

- ^ Woodger & Toropov, 2009 p. 270

- ^ "Lewis and Clark Trek". Archived from the original on Dec 8, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ "Founders Online: From Thomas Jefferson to Benjamin Smith Barton, 27 February 1803". founders.athenaeum.gov. Archived from the original on Apr 12, 2019. Retrieved Apr 12, 2019.

- ^ Gass & MacGregor, 1807 p. vii

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 pp. 79, 89

- ^ Duncan, Dayton; Burns, Ken (1997). Lewis & Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. pp. 9–ten. ISBN9780679454502.

- ^ Ambrose, Stephen (1996). Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American W. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 81, 87–91. ISBN9780684826974.

- ^ Jackson, 1993, pp.86–87

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 p. 13

- ^ Homser, James Kendall, 1903 p. 1

- ^ Kleber, 2001 pp. 509–x

- ^ Fritz, 2004 pp. 1–5

- ^ Ronda, 1984 p. 32

- ^ Miller, 2006 pp. 99–100, 111

- ^ Bennett, 2002 p. 4

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 p. 94

- ^ a b Saindon, 2003 pp. 551–52

- ^ a b Miller, 2006 p. 106

- ^ Woodger, Toropov, 2009 pp. 104, 265, 271

- ^ Lavander, 2001 pp. thirty–31

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 pp. 137-139

- ^ "May 14, 1804 | Discovering Lewis & Clark ®". www.lewis-clark.org. May 14, 1804. Archived from the original on March 20, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ Peters 1996, p. sixteen.

- ^ Allen, Lewis & Clark, Vol. 1, 1916 pp. 26–27

- ^ Woodger & Toropov, 2009 p. 142

- ^ Coues, Lewis, Clark, Jefferson 1893, Vol. 1 p. 79

- ^ Fritz, 2004 p. xiii

- ^ Fritz, 2004 p. xiv

- ^ "Bad River Encounter Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on August iii, 2020. Retrieved May xviii, 2020.

- ^ Fritz, 2004 pp. 14–xv

- ^ a b Ambrose, 1996 p. 170

- ^ Ronda, 1984 pp. 27, twoscore

- ^ Lavender, 2001 p. 181

- ^ Peters 1996, pp. 20–22.

- ^ Clark & Edmonds, 1983 p. 12

- ^ Allen, Lewis & Clark, Vol. one, 1916 pp. 81–82

- ^ Elin Woodger; Brandon Toropov (2009). Encyclopedia of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Infobase Publishing. pp. 244–45. ISBN978-1-4381-1023-3 . Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ a b c Lewis, Mailing Address; Astoria, Clark National Historical Park 92343 Fort Clatsop Road; Usa, OR 97103 Phone:861-2471 Contact. "History & Civilisation - Lewis and Clark National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". world wide web.nps.gov. Archived from the original on February 22, 2015. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- ^ "Lewis and Clark, Journey Leg 13, 'Ocian in View!', Oct eight – December 7, 1805". National Geographic Guild. 1996. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ^ a b Ambrose, 1996 p. 326

- ^ Clark & Edmonds, 1983 pp. 51–52

- ^ Harris, Buckley, 2012, p. 109

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 p. 330

- ^ a b Malloy, Mary (2006). Devil on the deep blue sea: The notorious career of Captain Samuel Hill of Boston. Bullbrier Printing. pp. vii, 46–49, 56, 63–64. ISBN978-0-9722854-1-4.

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 p. 334

- ^ Coues, Lewis, Clark, Jefferson 1893 pp. 902–04

- ^ "Meriwether Lewis is shot in the leg". History. A&E Goggle box Networks. Archived from the original on October xv, 2018. Retrieved Oct fourteen, 2018.

- ^ Peters 1996, p. thirty.

- ^ Uldrich, 2004 p. 82

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 p. 402

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 p. 483

- ^ Fritz, 2004 p. threescore

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 p. 409

- ^ Woodger & Toropov, 2009 p. 99

- ^ DeVoto, 1997 p. 552

- ^ Woodger, Toropov, 2012 p. 29

- ^ Fritz, 2004 p. 59

- ^ Uldrich, 2004 p. 37

- ^ Fresonke & Spence, 2004 p. 70

- ^ Fritz, 2004 p. 88

- ^ Gass & MacGregor, 1807 pp. 4, three

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 pp. 479–80

- ^ Lewis and Clark Journals Archived January thirty, 2009, at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ Pekka Hamalainen, "Lakota America, a New History of Indigenous Power," (New Haven: Yale Academy Press, 2019), pp. 129-131

- ^ a b c d Josephy, 2006 p. half-dozen

- ^ a b c d Allen, Lewis & Clark, Vol. 1, 1916 p. 52

- ^ a b c d Ambrose, 1996 p. 169

- ^ a b c d Woodger & Toropov, 2009 pp. 8, 337–38

- ^ Pekka Hamalainen, "Lakota America, a New History of Indigenous Power," (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), pp. 130-136

- ^ Harry Due west. Fritz (2004). "The Lewis and Clark Trek". Greenwood Publishing Group. p.14. ISBN 0313316619

- ^ Coues, Lewis, Clark, Jefferson 1893, Vol. 2 pp. 557–58

- ^ Lewis, Clark Floyd, Whitehouse, 1905 p. 93

- ^ Coues, Lewis, Clark, Jefferson 1893, Vol. 1 p. 229

- ^ Clark & Edmonds, 1983 p. 15

- ^ Coues, Lewis, Clark, Jefferson 1893, Vol. i p. 377

- ^ Clark & Edmonds, 1983 p. 16

- ^ Fritz, 2004 p. nineteen

- ^ Clark & Edmonds, 1983 pp. 16, 27

- ^ Ronda, 1984 pp. 258–59

- ^ Fritz, 2004 pp. 33–35

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 pp. 352, 407

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 p. 204

- ^ Ambrose, 1996, p. 418

- ^ Ambrose, 1996, p. 144

- ^ Bauder, Bob (March x, 2019). "Pittsburgh recognized as starting betoken for Lewis and Clark expedition". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review . Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ "Ulmus americana 'Lewis & Clark' PRAIRIE EXPEDITION". Plant Finder. Archived from the original on August 15, 2021. Retrieved Baronial xv, 2021.

- ^ Loomis & Nasatir 1967 pp. 382–86, map: p. 290

- ^ Ambrose, 1996 p. 70, 91

- ^ Woodger, Toropov, 2009 pp. 191, 351

- ^ "Sir Alexander Mackenzie | Scottish explorer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on June xv, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

Bibliography

- Allen, Paul (1902). History of the expedition under the control of Captains Lewis and Clark, Vol I. Toranto, George Due north. Morang & Co. Ltd.

- —— (1902). History of the expedition under the command of Captains Lewis and Clark, Vol II. Toranto, George Due north. Morang & Co. Ltd.

- —— (1902). History of the trek under the command of Captains Lewis and Clark, Vol Iii. Toranto, George Due north. Morang & Co. Ltd.

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (1996). Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West . Simon and Schuster, New York. p. 511. ISBN9780684811079.

- Bennett, George D. (2002). The United states Army: Issues, Background and Bibliography. Nova Publishers. p. 229. ISBN9781590333006.

- Bergon, Frank (1989). The Journals of Lewis and Clark. Penguin Classics, New York. ISBN0142437360.

- Clark, Ella E.; Edmonds, Margot (1983). Sacagawea of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Academy of California Press. p. 184. ISBN9780520050600.

- Cutright, Paul Russel (1969). Lewis and Clark: Pioneering Naturalists. Academy of Nebraska Press.

- Cutright, Paul Russell (2000). Contributions of Philadelphia to Lewis and Clark History. Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. p. 47. ISBN9780967888705.

- DeVoto, Bernard Augustine (1997) [1953]. The Journals of Lewis and Clark. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 504. ISBN0-395-08380-10.

- —— (1998). The Course of Empire. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 647. ISBN9780395924983.

- Fenelon, James; Defender-Wilson, Mary Louise (1985). "Voyage of Domination, "Buy" every bit Conquest, Sakakawea for Savagery: Distorted Icons from Misrepresentations of the Lewis and Clark Expedition". Wicazo Sa Review. University of Minnesota Press. xix (1): Wicazo Sa Review, 85–104. doi:ten.1353/wic.2004.0006. JSTOR 1409488. S2CID 147041160.

- Fresonke, Kris; Spence, Mark (2004). Lewis and Clark. University of California Press. p. 290. ISBN9780520228399.

- Fritz, Harry W. (2004). The Lewis and Clark Expedition . Greenwood Publishing Grouping. p. 143. ISBN978-0-313-31661-half-dozen.

- Furtwangler, Albert (1993). Acts of discovery: visions of America in the Lewis and Clark journals . Academy of Illinois Press. ISBN978-0-252-06306-0.

- Gass, Patrick; MacGregor, Carol Lynn (1807). The Journals of Patrick Gass: Member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Mount Press Publishing. p. 447. ISBN9780878423514.

- Gray, Edward (2004). "Visions of Another Empire: John Ledyard, an American Traveler across the Russian Empire, 1787–1788". Journal of the Early Republic. Academy of Pennsylvania Press. 24 (3): 347–380. JSTOR 4141438.

- Harris, Matthew Fifty.; Buckley, Jay H. (2012). Zebulon Pike, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. University of Oklahoma Press, 256 pages. ISBN9780806188317.

- Josephy, Alvin M. Jr.; Marc, Jaffe, eds. (2006). Lewis and Clark Through Indian Eyes. Random Business firm Digital, Inc. p. 196. ISBN9781400042678.

- Jackson, Donald (1993) [1981]. Thomas Jefferson & the Stony Mountains: Exploring the Due west from Monticello. Academy of Oklahoma Printing. ISBN978-0-8061-2504-6.

- Kleber, John (2001). The Encyclopedia of Louisville. University Press of Kentucky. p. 509. ISBN978-0-8131-2100-0.

- Lavender, David Sievert (2001). The Mode to the Western Sea: Lewis and Clark Across the Continent. Academy of Nebraska Press. p. 444. ISBN9780803280038.

- Loomis, Noel M; Nasatir, Abraham P (1967). Pedro Vial and the Roads to Santa Fe. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN9780806111100.

- Miller, Robert J. Miller (2006). Native America, Discovered And Conquered: Thomas Jefferson, Lewis & Clark, And Manifest Destiny. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 240. ISBN9780275990114.

- Peters, Arthur K. (1996). Seven trail west. Abbeville Press. ISBNone-55859-782-iv.

- Saindon, Robert A. (2003). Explorations Into the World of Lewis and Clark, Volume 3. Digital Scanning Inc. p. 528. ISBN9781582187655.

- Schwantes, Carlos (1996). The Pacific Northwest: an interpretive history. University of Nebraska Press. p. 568. ISBN978-0-8032-9228-4.

- Rodriguez, Junius (2002). The Louisiana Purchase: a historical and geographical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, California. p. 513. ISBN978-one-57607-188-five.

- Ronda, James P. (1984). Lewis & Clark among the Indians. Academy of Nebraska Press. p. 310. ISBN9780803289901.

- Uldrich, Jack (2004). Into the unknown: leadership lessons from Lewis & Clark's daring due west adventure. AMACOM Div American Mgmt Assn. p. 245. ISBN0-8144-0816-8.

- Woodger, Elin; Toropov, Brandon (2009). Encyclopedia of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Infobase Publishing. p. 438. ISBN978-0-8160-4781-9.

Primary sources

- Lewis, Meriwether; Clark, William (2004). The Journals Of Lewis And Clark. Kessinger Publishing. p. 312. ISBN9781419167997. E'books, Full view[ full citation needed ]

- Lewis, Meriwether; Clark, William; Floyd, Charles; Whitehouse, Joseph (1905). Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804-1806, V.half-dozen. Dodd, Mead & Company, New York. p. 280.

- Lewis, Meriwether; Clark, William (2003). Bergon, Frank (ed.). The Journals of Lewis & Clark. Penguin. p. 560. ISBN9780142437360.

- Lewis, Meriwether; Clark, William (1815). Travels to the source of the Missouri river and beyond the American continent to the Pacific ocean. Performed past order of the government of the United States, in the years 1804, 1805, and 1806. Past Captains Lewis and Clarke. Published from the official report, and illustrated by a map of the route, and other maps. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown.

- "Review of Travels to the Source of the Missouri River ... ". The Quarterly Review. 12: 317–368. January 1815.

- Lewis, William; Clark, Clark (1903). Hosmer, James Kendall (ed.). History of the Expedition of Helm Lewis and Clark, 1804-5-6, Book 1. A. C. McClurg & Company, Chicago. p. 500.

- Coues, Elliott; Lewis, Meriwether; Clark, William; Jefferson, Thomas (1893). History of the expedition under the command of Lewis and Clark: Volume i. Francis P. Harper, New York. p. 1364. ISBN9780665562136.

- ——; Lewis, Meriwether; Clark, William; Jefferson, Thomas (1893). History of the expedition nether the command of Lewis and Clark: Volume 2. Francis P. Harper, New York. p. 1364.

- ——; Lewis, Meriwether; Clark, William; Jefferson, Thomas (1893). History of the expedition under the command of Lewis and Clark: Volume 3. Francis P. Harper, New York. p. 1298.

- ——; Lewis, Meriwether; Clark, William; Jefferson, Thomas (1893). History of the expedition under the command of Lewis and Clark: Volume 4. Francis P. Harper, New York. p. 1298.

- Jackson, Donald Dean (1962). Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: with related documents, 1783-1854 . Academy of Illinois Press (Original from the Academy of Virginia). p. 728.

- Lewis, Meriwether; Clark, William (2004). Moulton, Gary East. (ed.). The Definitive Journals of Lewis & Clark. University of Nebraska Press. p. 357. ISBN9780803280328.

Farther reading

- Steven E. Ambrose (1996). Undaunted Backbone, Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West . Simon and Schuster Paperbacks. ISBN9780684826974.

- Bassman, John H. (2009). A Navigation Companion for the Lewis & Clark Trail. Volume i, History, campsite locations and daily summaries of trek activities. John H. Bassman.

- Betts, Robert B. (2002). In Search of York: The Slave Who Went to the Pacific With Lewis and Clark. ISBN0-87081-714-0.

- Clark, William; Lewis, Meriwether. The Journals of Lewis and Clark, 1804–1806.

- Burns, Ken (1997). Lewis & Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery. ISBN0-679-45450-0.

- Fenster, Julie M. (2016). Jefferson's America: The President, the Buy, and the Explorers Who Transformed a Nation. Crown/Archetype. ISBN978-0-3079-5654-5.

- Hayes, Derek (1999). Historical Atlas of the Pacific Northwest: Maps of Exploration and Discovery: British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, Alaska, Yukon. Sasquatch Books. p. 208. ISBN978-1570612152.

- Gen. Thomas James (February 11, 2018). Three Years Amidst the Indians and Mexicans. ISBN978-1985208711.

- Gilman, Carolyn (2003). Lewis and Clark: Across the Divide. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books. ISBN978-1588340993.

- Schmidt, Thomas (2002). National Geographic Guide to the Lewis & Clark Trail. ISBN0-7922-6471-1.

- Tubbs, Stephenie Ambrose (2008). Why Sacagawea Deserves the Twenty-four hour period Off and Other Lessons from the Lewis and Clark Trail. Academy of Nebraska Press.

- Wheeler, Olin Dunbar (1904). The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804–1904: A Story of the Great Exploration Across the Continent in 1804–6. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 377.

External links

- Total text of the Lewis and Clark journals online – edited by Gary E. Moulton, University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- "National Archives photos dating from the 1860s–1890s of the Native cultures the expedition encountered". Archived from the original on Feb 12, 2008.

- Travel the Lewis and Clark Expedition, a National Park Service Detect Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- "History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark: To the Sources of the Missouri, thence Across the Rocky Mountains and downwards the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean" published in 1814; from the Globe Digital Library

- Lewis & Clark Fort Mandan Foundation: Discovering Lewis & Clark

- Corps of Discovery Online Atlas, created by Watzek Library, Lewis & Clark Higher

- Lewis and Clark Expedition Maps and Receipt. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Volume and Manuscript Library.

- William Clark Field Notes. Yale Drove of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- Louis Starr Collection Concerning the Field Notes of William Clark. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_and_Clark_Expedition

Posted by: taylorsockle.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Plants And Animals Did Lewis And Clark Discover"

Post a Comment